Photo by the Possibility Lab.

The University of California’s Possibility Lab, in collaboration with the TODEC Legal Center, has produced a report that explores how Latino immigrant farm, warehouse and service workers in the Inland Empire and Coachella Valley perceive and experience health, or its absence, along with the challenges they face in attaining it.

The study is part of a larger research initiative called the Firsthand Framework for Policy Innovation, dedicated to creating ground-breaking policies based on the idea that “the people who are closest to social problems that require innovative policy are the ones who know the most about how to solve those problems” said Dr. Naomi Levy, Director of Community Engaged Research at the Possibility Lab and Professor of Political Science at the Santa Ana University, during the presentation of the fieldwork results last Fall in the Coachella Valley Library.

With this concept in mind, the researchers facilitated nine focus group discussions and three town halls throughout the region, gathering 1,534 first-hand indicators that allowed them to establish the presence or absence of health in the communities. Many reflect the latter: “People get sick because some companies put too many chemicals on their plants or vegetables (Low Desert).”

The researchers divided the study area into three regions. The Low Desert includes the communities of Thermal, Oasis, Coachella, Mecca, Indio, Blythe and North Shore. The West End encompasses Perris, Moreno Valley, Lake Elsinore, Temecula, San Jacinto, Homeland, Nuevo, Menifee, Corona, Fallbrook, Riverside, Jurupa Valley, Banning, Beaumont, Hemet, San Bernardino, Fontana and Ontario. Lastly, the High Desert covers Hesperia, Victorville, Apple Valley, Barstow, Adelanto, Phelan and Muscoy.

Photo by the Possibility Lab.

“[First-hand indicators] are the signs and signals people are already using in their daily lives to figure out how things are going for them and for their communities […] the things that they are already seeing and hearing and feeling in their daily lives that tell them whether or not they have health. By collecting these, we can then prioritize their voices. We can tap into the expertise that they themselves possess,” explained Dr Levy.

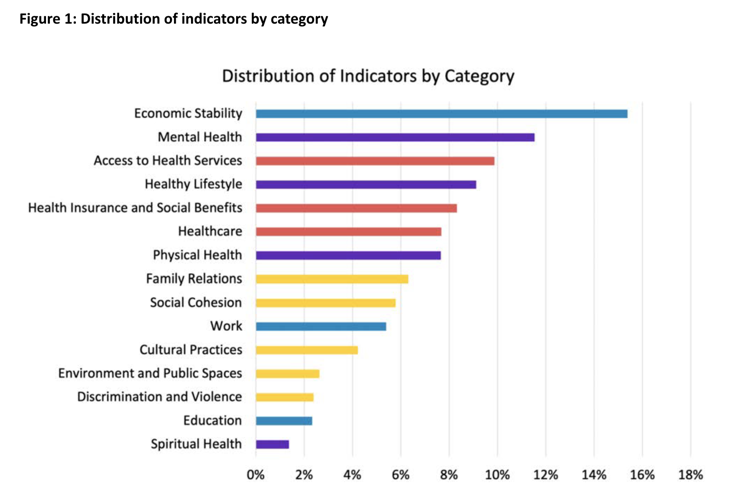

The 1,534 indicators were later segmented into four dimensions: economic concerns, including economic stability, work, and education; individual health, which encompasses mental health, healthy lifestyle, physical and spiritual health; health systems involving access to health services, healthcare, insurance and social benefits; and social dynamics incorporating family relations, social cohesion, cultural practices, environment and public spaces, and discrimination and violence.

“One of the most prominent categories that basically represented about 15% of the indicators is economic stability,” said senior researcher Dr. Fiorella Vera-Adrianzén during the event. She pointed to an example, namely the indicator stating, "You can’t have a good diet because healthy food is very expensive," emphasizing financial stability's crucial role in overall health.

Graphic by the Possibility Lab.

“How can a farm worker that feeds not only our region but our state and our country and other countries can’t even afford food for our own,” inquired Luz Gallegos, TODEC Executive Director, in a mini-documentary produced to share the journey of developing the research and the live experience of those who shape it.

According to the California Department of Food and Agriculture, the state produces more than one-third of the nation's vegetables and over three-quarters of its fruits and nuts, making it a vital player in the U.S. food supply. The Public Policy Institute of California found that “90% of workers in some agricultural and landscaping jobs are Latino,” with a median wage of $13 per hour. The University of California, Merced, estimates that “75 percent of California's agricultural workers are undocumented.”

Despite being a vital workforce, Latinos encounter considerable vulnerabilities, particularly in the healthcare sector. The study found that in the Low Desert region, where the majority of the communities reported more than 90% of their residents identify as Latino, uninsured rates run as high as 21% in the case of Oasis, along with one of the lower median household incomes of $25,335, making healthcare a considerable challenge.

Since January 1, 2024, immigration status is no longer a requirement to qualify for MediCal benefits, making it possible for undocumented immigrants to apply for the program. Nonetheless, applicants must meet the income limits to qualify. In this regard, a family of “1” must meet an income limit of $20,783 per year. Thus, a single person from Oasis earning a median household income of $25,335 is unlikely to qualify for the benefits.

Photo by the Possibility Lab.

“We’ve heard stories of farm workers that they had their spouses kill themselves because they didn’t have access [to mental health services]. They didn’t know how to detect what depression looks like. With the Possibility Lab, we are documenting their struggle into a report that we hope brings justice to our most vulnerable workforce […],” said Gallegos.

Among the four dimensions examined in the analysis, mental health emerged as a significant concern, representing 12% of the findings. Participants highlighted how mental health challenges profoundly affect their daily lives, “especially in the West End and High Desert, where many residents lack access to affordable care,” according to the report. They pointed to factors such as fear of deportation, stress and anxiety linked to immigration status, compounded by the difficulty of accessing mental health services.

The study also estimated that six to 10 thousand Purépecha, an Indigenous group from Michoacan, Mexico, live in this region, preserving their ancestral traditions and language. However, this commitment can also pose difficulties, as many in the community “do not understand English and have limited knowledge of Spanish, making it difficult for them to access goods and services.”

The findings were presented in a panel featuring regional leaders and experts, including V. Manuel Perez, Riverside County Supervisor; Kim Saruwatari, Director of Public Health at Riverside University Health System; Luz Gallegos, Executive Director of TODEC; Lilia García-Brower, California Labor Commissioner; Dr. Fiorella Vera-Adrianzén, Senior Researcher; and Dr. Naomi Levy, Director of Community-Engaged Research at the Possibility Lab and Professor of Political Science at Santa Ana University.

“Overall, the data suggest that health for Latino immigrant workers is not just related to medical issues, but is deeply intertwined with economic, psychological, and social factors,” the paper described.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.