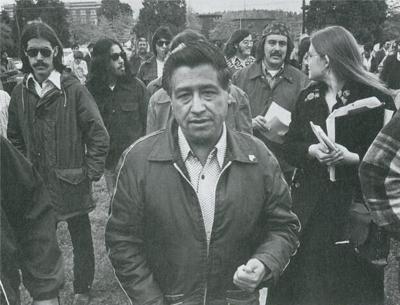

A first-generation American, Cesar Chavez was born on March 31, 1927. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Every year, the last day of March is known as César Chávez Day. The U.S. federal commemorative holiday, proclaimed by former President Barack Obama in 2014, is intended to celebrate the birth and legacy of César Chávez. Today, more than three decades since his death in 1993, the civil rights and labor movement activist continues to be among the most respected and well-known Latino leaders. Yet, there is an undeniably complicated history surrounding Chávez's opposition to undocumented immigration—a stance that many argue undermines his image as a beloved union organizer.

On one hand, Chávez’s leadership in advocating for farmworkers' rights, through hunger strikes, organizing grape boycotts and leading the United Farm Workers (UFW)—played a pivotal role in improving labor conditions. However, it is equally important to acknowledge the part of his work that wasn’t always progressive, including his anti-immigrant sentiments and practices that, especially today, are important to be critical of and learn from.

In a 1974 interview with La Paz, Chávez accused agricultural growers and authorities of exploiting undocumented Mexican immigrants as strikebreakers to undermine the UFW union. He claimed that these "illegal workers" were being smuggled into the U.S. to break strikes and weaken the union's efforts.

During the interview, Chávez claimed that undocumented migrants were entering the country in large numbers. “We estimate that 60 to 70 percent of the farmworkers in California–of the resident workers—are out of the job because of the wetbacks,” he said. Chávez further asserted that many immigration checkpoints were left "unmanned" by the government intentionally, suggesting this was a deliberate strategy to undermine labor strikes. He also noted that many Mexican citizen farmworkers were frustrated by the influx of undocumented workers, fearing they would take jobs and disrupt union efforts.

In response to this issue, Chávez initiated the ‘Illegals Campaign.’ Launched during the mid-70s, the campaign echoed similar sentiments to modern-day anti-immigrant talking points. This initiative included organizing patrols along the U.S.-Mexico border, which were led by Chávez's cousin, Manuel Chávez. These patrols sought to prevent undocumented immigrants from entering the U.S. and potentially undermining UFW's labor actions.

Manuel Chávez led some of the “wet lines,” which Chávez fully supported and encouraged United Farm Worker members to join, with the argument that immigrants were often driving down wages, and crucially, being used as strikebreakers. Members of these wet lines would patrol the Southern Border, preventing undocumented workers from passing into the United States. They were doing the work of the Border Patrol.

“A year ago, we assigned many of our organizers to do nothing but to check on the law violators coming from Mexico to break our strikes,” Chávez said in a public hearing with members of Congress in 1969. “We gave the Immigration and Naturalization Services and the Border Patrol stacks and stacks of information. They did not pull workers out of struck fields. Today there are thousands of workers being imported in the strike scene. In fact. I would say the green carders and illegal entries make up ninety percent of the workforce at the struck ranches. This is why we are forced to boycott.”

Other renowned Chicano leaders, such as Dolores Huerta, have come to the defense of Chávez. Huerta was once quoted as saying, “that’s just how Chicanos talked in those days.” Even the United Farm Workers have said that Chávez's views on immigrants and immigration as “nuanced.”

However, despite these controversies, Chávez maintained that his actions were justified, viewing undocumented workers as competitors who threatened the livelihoods of unionized farmworkers. It wasn’t until the 1980s that Chavez began to soften his position on immigration, especially as he saw the human suffering and exploitation faced by many undocumented workers. He eventually supported immigration reform and legalization efforts, including the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986.

Chávez's legacy, widely revered as a civil rights leader and champion of farm workers, is undeniably complicated. While his dedication to improving the lives of farm workers brought about transformative rights for many, it is also true that his views on immigration were harmful.

Today, as the immigrant community is under constant attack, it is important to be critical and have hard but honest conversations, even with the people we admire the most, because before being our icons, they were human, and perhaps more often than thought, flawed humans.

Depicting leaders like Chávez can be difficult, especially for a generation of Latinos who witnessed the positive impact of his organizing and labor work. For many, Chávez represents the first widely recognized or most respected Latino leader. But turning our heads away from the complex human he was does not keep his legacy intact but puts Chávez in a box, where an idol can only be an idol and not human.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.