L.A. artist Barbara Carrasco’s 80-foot landmark 1981 mural, “L.A. History: a Mexican Perspective,” is permanently displayed at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles’s newest addition, NHM Commons. Photo by Abelardo de la Peña Jr.

Located on the western end of the Natural History Museum, a new wing called NHM Commons has opened, welcoming a new generation of students and other guests.

The new space, a community hub that is free to the public, is highlighted by the expansive Judith Perlstein Welcome Center. The space, airy and well-lit, features two distinctive, one-of-a-kind exhibitions. Both have undergone unprecedented journeys to get to where they are now housed.

On the north side is Gnatalie, a long-necked dinosaur, 75 feet long from tail to nose, the only green-colored fossil on the planet. It’s part of the dinosaurs, dioramas, insects, rocks, birds and historical artifacts found at the museum. But we’re not here to talk about that.

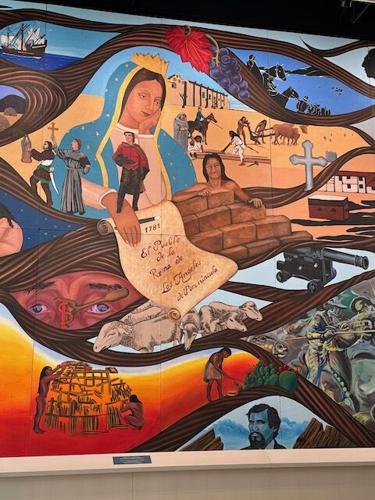

Museum visitors view a section of “L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective” that several scenes several scenes of Gabrieleño/Tongva life and a detail of L.A.’s original name, El Pueblo de la Reina de Los Angeles de Porciúncula. Photo by Abelardo de la Peña Jr.

On the other side is another historical treasure, not as old as Gnatalie’s bones, but one that has also been hidden for many years, not under dirt and rocks but because of the close-mindedness of bureaucrats. The 16-by-80-foot mural “L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective” was painted on 43 Masonite and wood panels. Its formidable creation and rocky survival is a story of creativity, art, censorship, truth, justice, perseverance and ultimately, accomplishment and triumph.

A young Chicana's artistic vision

The mural is a vividly colorful and intricate series of 51 scenes depicting a chronological history of Los Angeles. The creator is Barbara Carrasco, a Chicana artist who applied the first brush strokes 43 years ago. It was commissioned by the city’s Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) and intended to be completed and displayed for L.A.’s Bicentennial in 1981.

“I was 26 years old at the time, employed by the CRA along with artists like Carlos Almaraz, Frank Romero, John Valadez, Judithe Hernández and Dolores Guerrero Cruz,” remembers Barbara, a few weeks before the unveiling of the mural at the museum. “They wanted to install a mural on the MacDonalds on Broadway. I said I would love to do it but thought they would go with the older artists because I was the youngest. They asked me if I would be willing to do it, and I said I would love to!”

Barbara Carrasco working on her mural at Union Station. L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective. Photo by Shifra Goldman

She was told that the mural could be on anything, as long as it was about L.A. “I thought the city’s history would be a good thing to delve into, but I didn’t know that it would turn into a big can of worms,” she says.

Awarded seven thousand dollars to design, paint and mount the mural, Barbara considered herself a commissioned artist, even though she was an employee of the CRA. Once she began sketching out the mural, she placed a copyright symbol on it, claiming ownership of the art. It was a prescient move that would significantly impact the work of art.

Everything about L.A. in one place

One of Barbara's first steps after receiving the commission was researching the city, which took her to the Natural History Museum. “I met with Bill Mason, who was the head historian. My God, he knew everything about L.A.,” she exclaimed. “He opened his archives to me, saying, ‘Barbara, you can borrow any of these photos of early L.A.,’ like the Red Car, the construction of City Hall and more.

“Then he told me the thing that inspired me the most … the original name of the city … El Pueblo de la Reina de los Angeles de Porciúncula … the town of the Queen of Angels of Porciúncula,” she said. “As soon as he said, ‘Queen of Angels,’ I immediately got the idea of having a woman with braided hair as her crown, with flowing hair, a real organic mural. That’s how the original sketch came about.

“I didn’t think they were going to approve it … it was a crazy sketch, but it’s a cool idea to put all the different vignettes of L.A. history in it,” she remembers.

Each of the 43 Masonite-and-wood panels shows vivid highlights of L.A.’s story. Here, La Virgen de Guadalupe is encircled by images of the Tongva/Gabrieleño people; the arrival of the Spaniards; the Pobladores, who first settled the pueblo; the building of Los Angeles’ the fight between Mexico and the United States; a cattle brand set before the eyes of a Native American; and a portrait of Tiburcio Vázquez. Photo by Abelardo de la Peña Jr.

In a relatively short time, she chose the historical vignettes that would be part of the mural: prehistoric L.A. and the La Brea Tar Pits; the life of Gabrieleño/Tongva; Mission San Gabriel; the fight over L.A. during the war between Mexico and the U. S.; the building of the railroad; Union Station; Grand Central Market; and much more.

Once the CRA board approved the sketch, she began painting the mural in L.A. City Hall’s East Building, working alongside other artists, including Yreina Cervantez, Glenna Boltuch Avila and Ron Sakai, who are credited on the mural, along with Gilbert ‘Magu’ Luján and members of the East Los Streetscapers and a group of 17 youth workers from the city’s Summer Youth Employment Program.

The group worked hard to complete the work on time for the Bicentennial Celebration, hoping the mural would still be displayed for the upcoming 1984 Olympic Games. Alongside the historical elements of the mural, the work featured her family, friends and collaborators, who served as models, including her sister Frances, the mural’s primary figure, the Indigenous woman with the long, braided hair.

Censorship masked as ‘suggestions’

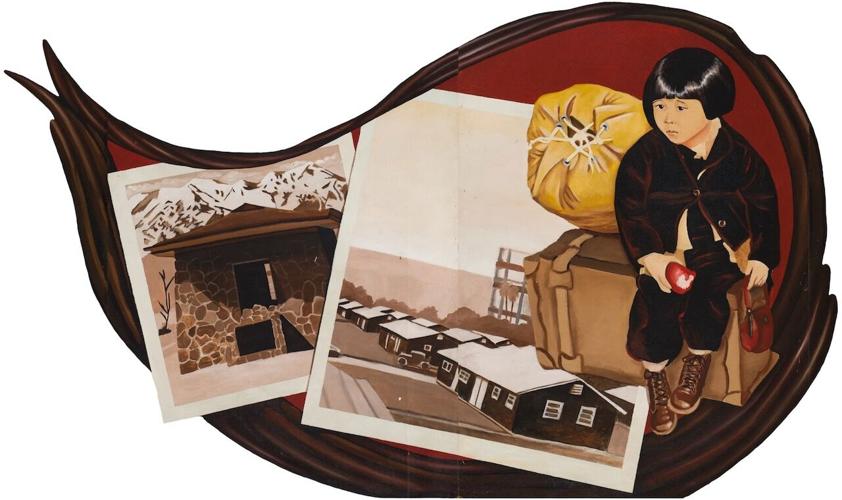

“Then, all of sudden, the shit hit the fan,” recounts Barbara. CRA officials objected to 17 of the 51 vignettes , including Japanese internment camps, the 1871 lynching of Chinese workers, farm workers laboring, the Zoot Suit Riots and ironically, the whitewashing of David Alfaro Siqueiros’s outdoor mural América Tropical (1932) overlooking Olvera Street.

“They had the sketch on the wall, with segments outlined in red and purple. The red were things that would definitely have to be taken out, the purple were suggestions for vignettes to be eliminated,” she said. “I told them that was some bullshit. They said they weren’t doing anything, careful about not using the word ‘censorship. They asked, ’Why do you want to put anything about the Japanese internment in there? They don’t want to be reminded of it.’”

One of the images that was attempted to be censored, a Japanese incarceration scene. Photo courtesy California Historical Society / LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes

She invited three local Japanese organizations to view the mural in progress, including the Little Tokyo People’s Rights Organization. “They wrote incredible letters of support, saying that although it was a negative chapter in their lives, it had to [be] told. It’s critical, to tell the truth about L.A. and about what has happened,” she told me.

Vowing not to take anything out, progress on the mural slowed down, and it ultimately was not completed in time for the Bicentennial. However, there was hope it would be exhibited in time for the Olympics.

But while the debacle with the CRA was still playing out, Barbara discovered panels were being moved from City Hall East to a warehouse. She quickly moved the mural to the East L.A. headquarters of the Community Service Organization and later to the United Farm Workers headquarters in Keene, California, where she had a longstanding relationship with the union’s leadership, including César Chávez and Dolores Huerta.

Still, the CRA continued in their attempts to take control of the mural, maintaining that the agency deserved complete ownership, with Barbara and her attorneys arguing the right of the artist to protect her art from censorship. Finally, in 1983, Barbara was awarded ownership: as the commissioned artist, she had control over her art alone.

The mural emerges, then is hidden away

Stored at the UFW headquarters, the entire mural lay unseen until 1990, when she was invited to have it displayed at the Los Angeles Festival, a 16-day celebration of the Pacific Rim’s arts and culture, with more 1,300 artists from more than 25 countries participating, growing out of the 1984 Olympic Arts Festival.

“David Botello, one of the members of the Streetscapers, told festival organizer Peter Sellers about it. It was selected, and they displayed it at Union Station,” says Barbara.

The mural’s panels were shipped to Paramount Studios in Hollywood to be cleaned after years in storage. “They each weighed about 70 pounds. I’d put them on the floor; then we were all cleaning … my stepfather, my sisters, a bunch of other people. It was a lot of physical labor,” she says.

At long last, the public could view the mural in its entirety, high above the Ticketing Concourse at Union Station, where it was viewed in its entirety for the very first time. “It was wonderful,” exclaims Barbara. “And then it came down,” she adds, ruefully.

And then, it returned to storage, only to emerge occasionally. “A third of it was shown at the Autry Museum; a third was shown at Otis Art Institute. It was selected to be part of a show called ‘L.A. Hot & Cold’ at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT),” she says.

Bringing the mural back to light

I first met Barbara in 2017 and became aware of her mural for the first time. I’d just started working at LA Plaza de Cultura de Artes, the downtown museum and cultural hub, and her mural was an integral part of LA Plaza’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA exhibition called “Murales Rebeldes: Chicana/o Murals in Siege.” It was a landmark show presenting stories of eight Chicana/o murals that were censored, neglected, whitewashed, and even destroyed.

As part of the exhibition, co-organized by LA Plaza and the California Historical Society, the plan was to install the mural once again at Union Station in Los Angeles. I didn’t know much about the mural then, catching up fast due to its importance as a unique and vital record of the city’s history, emphasizing L.A.’s marginalized groups and lesser-known events. I also learned about Barbara’s seemingly unending struggle to have the mural displayed for the public to see. And it wasn’t getting any easier.

Continuing its tumultuous trajectory since its inception, the mural was again caught in a struggle. Union Station’s administration was taking its time giving the go-ahead to install the mural, and as it got closer, I received multiple calls from Barbara asking what was going on. Finally, permission was granted and “LA History: A Mexican Perspective” was mounted for a brief period, to great acclaim.

Crowds of people viewed the mural during its two-week run. The exhibition was covered extensively in the media, including the L.A. Times, CBS News, Latino USA, NBC News and more. “Someone said to me, ‘You’re hot, Barbara, you’re getting so much press,’ and I was glad because otherwise it would be covered up again. It's like a big wave; it's cyclical,” recalls Barbara.

But it didn’t stay covered up for long, catching the attention of the leadership of the Natural History Museum, one of the places that Barbara, and the mural, began their journey.

Back to where it all began

In 2018, less than six months after being displayed at Union Station, its entire full length was shown in a museum gallery setting for the first time. In the Natural History Museum exhibition titled “Sin Censura: A Mural Remembers L.A.,” the mural was on view for six months, on loan from Barbara. The installation included a digital touchscreen, allowing visitors to explore the vignettes depicted in the mural and behind-the-scenes looks at the making of the mural. Check out the virtual gallery, where you can view the mural’s vignettes online and get information about each one.

Barbara remembers the museum had a series of luncheons to generate interest in the mural. “This woman, Vera Campbell, was sitting in front of me. I was telling her the story of the mural, talking about the kids and their contributions. That sparked her interest. She told me, ‘I love the way you talk about the students who were part of the project.’ I said, ‘Well, I’m really proud of them. I saw them coming in real shy, but when I told them that [the mural] was not my history, it’s our history, I could see the expression on their faces change.

In March 2020, the Natural History Museum announced the acquisition of the mural, the funds provided by a grant from the Vera R. Campbell Foundation.

Home at last

Finally, “L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective” had found a permanent home, at the place she visited on school field trips and as a Girl Scout, where she learned much about the city she lived in, where people can witness the history of their city, from the perspective of a courageous, self-assured and assertive Chicana.

I asked her, “What makes you most proud of this journey?”

“Well, I think what I’m most proud of is fighting for the integrity of the mural. People would say to me, ‘Why do that?’ I think that history is important. And we have to really honor the history by telling the truth about it.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.