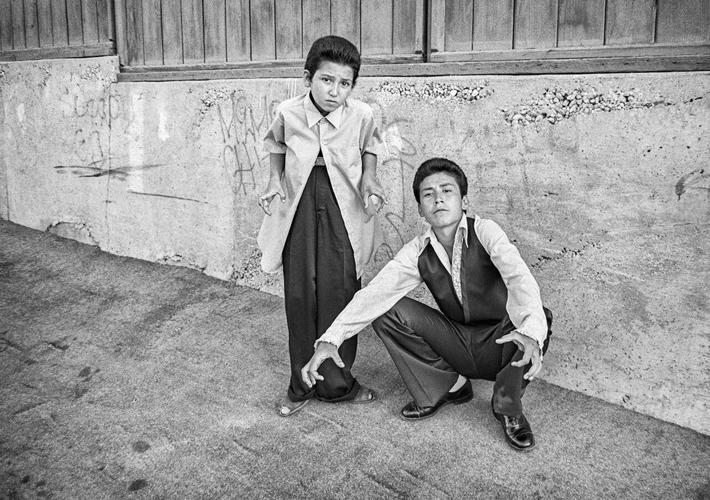

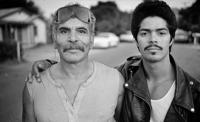

"WS 18th Street” Pico Union, 1982. Photo by Merrick Morton

On a recent bright and sunny afternoon, the doors of Eastern Projects, an art gallery located in Chinatown, have just opened. I’m the only one there besides the receptionist, Adriana, waiting on photographer Merrick Morton, whose exhibition “Un-Rehearsed" is on view on the gallery’s spacious walls.

I ask her how the exhibition’s going, and she tells me that it was a busy weekend. The family of one of the people pictured in the 84 photographs visited the eight-year-old gallery and they were ecstatic.

Just then, Merrick walks in, tall and quiet, camera slung across his shoulder. Adriana tells him about the family’s visit and he seems pleased. “What’s most interesting to me about this show is when I hear that someone comes in who is in one of the photographs or someone from their family,” he tells me.

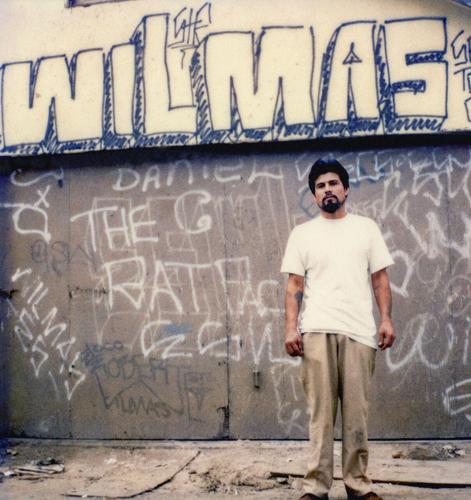

The photograph, “Cachy” East Side Wilmas, 1982, is a favorite of mine, taken in my hometown, Wilmington AKA Wilmas, and it was his family that came to visit after I’d posted the photograph on a Facebook group page. That’s where Merrick and I shared studio space in the early 1980s. It was a converted office, really, located above the Rexall Drugstore on the corner of Avalon Boulevard and Anaheim Street.

"Cachy” East Side Wilmas, Wilmington, 1982. Photo by Merrick Morton

I veered toward photojournalism, with traditional portraits and the occasional weddings and quinceañeras helping out with expenses.

His photography was way different from mine. Merrick’s shots were of teenage and early 20s youth, Mexican Americans dressed in distinctive style, posing fiercely with heads tilted back or crouching down and flashing hand signs.

Cholos and cholas. Hard-core gangbangers and their companions. Hard-looking men and women who I’d pass on the streets, but who weren’t part of my scene.

“When I was young, my mother took me to see the play "Zoot Suit," and that was an inspiration,” said Merrick. The late 70s photo work by famed Chicano artist and muralist John M. Valadez was another.

Merrick was, and still is, a quiet guy, so I didn’t ask about his work, only admired it. Plus, he worked different hours at the studio, me during the day between my regular work and on weekends, he mostly at night.

“Brother & Sister” Chiapas, Mexico, 1987. Photo by Merrick Morton

After a couple years, I gave up the studio to take on a full-time job and he moved on. We kept in touch, and though I’ve worked in and out of photography throughout my career, he’s maintained a steady rise, expanding his street photography to other neighborhoods, include East and Southeast L.A., Watts and downtown, shooting not only Mexican American gangs and gang members, but also in Black neighborhoods and Mexico, publishing his impactful photos in the LA Weekly, Rolling Stone magazine and other publications.

His work caught the attention of the movie industry, who at the time began to take interest in different cultures and subcultures. He began as a special still photographer on the sets of the iconic Luis Valdez-directed “La Bamba.”

“I was able to show some of my gang work and Mexico photos to the producer, Taylor Hackford. They already had a still photographer working for them, so they hired me as a second photographer,” he remembered.

”Dreamer” Dog Patch, Downey, 1982. Photo by Merrick Morton

He went on to bring his distinctive style to more movies, including “Blood In, Blood Out,” “Colors,” “Straight Outta Compton” and many, many more, garnering multiple International Cinematographers Guild nominations for Excellence in Unit Still Photography, Movies. He and his wife, Robin Blackman, also co-founded Fototeka, at the time one of the few galleries devoted to photography in Los Angeles, located in a Echo Park

He continues to shoot on set for both Oscar-winning movies and Emmy-winning TV series, but most recently it’s been his street portraiture that has gained the attention of a wide audience, thanks to his two Instagram accounts, @MerrickMortonPhoto, with 70K followers, and @MerrickMortonPhotos, a more recent account created by Merrick after Instagram took down his @MerrickMortonPhoto account, stating that his photos violated its community guidelines on violence or dangerous organizations.

Besides taking on a new life on Instagram and his website, his images are included in a recently-published book detailing the making and impact of “Blood In, Blood Out.” What’s more, he, along with noted street photographers Estevan Oriol, Suitcase Joe, and Frankie Orozco, among others, formed a collective called The L.A. Six, recently displaying their work at the Torrance Art Museum.

A couple of weekends ago, his photographs were projected on an 80-feet wide by three stories tall building in Chinatown as part of Projecting LA 2024, a one-of-a-kind public photography event celebrating street, documentary and news stories. And coming later this spring is the publication of his own photo book called "Clique: West Coast Portraits from the Hood." He’ll be traveling to Mexico City soon to begin a street portraiture project along with Mexican street photographer Chito Banda.

Merrick Morton, photographed at Eastside Projects, where his solo show “Un-Rehearsed” is currently on exhibition. Photo by Abelardo de la Peña Jr.

But for now, growing attention is on this collection of mostly black and white photos, starkly but elegantly displayed in black frames. This is his first solo show, and he explains the title, “Un-Rehearsed,” which he got with the help of neighbor and friend.

“Contrary to the [film] industry I’m in, where everything is rehearsed and rehearsed again, this work isn’t,” he says. “Even when you're searching for something [in particular], when you're a street photographer, you don't know what’s around the next corner.”

Responses have been edited for clarity and brevity.

When did you first take an interest in photography?

I got first involved with photography probably when I [was] eight or nine years old. I used to have one of those little Kodak Brownie cameras and set up little still scenes with my army men and little toys and stuff. I think probably in junior high, at 13 or 14 years old, my father got me a single lens reflex, and I began shooting for the [Hartman Junior High in Woodland Hills] school newsletter, mostly sports things. My father, Danny Morton, was for a time an actor under contract for Universal. I was always interested in photography, but I really wanted to become an actor, too. But I stuttered, so that stopped that, and I was also very shy. My father was also a good artist, so I grew up in that environment, too, so I guess I just grew into becoming a photographer.

Did you take any photography classes?

I took one or two semesters in high school, and I didn't do very well because I sort of shot what I wanted to shoot [instead of the assignments]. I was a high school dropout. I took some junior college classes, just of certain subjects that would interest me and then after I would lose interest I would drop out. A friend who was going to Cal State Northridge was taking a photography class, and when he transferred to Cal State LA, I was able to attend those classes even though I wasn't enrolled. But I needed a place to print, and the instructor was nice enough to let me go and print my work.

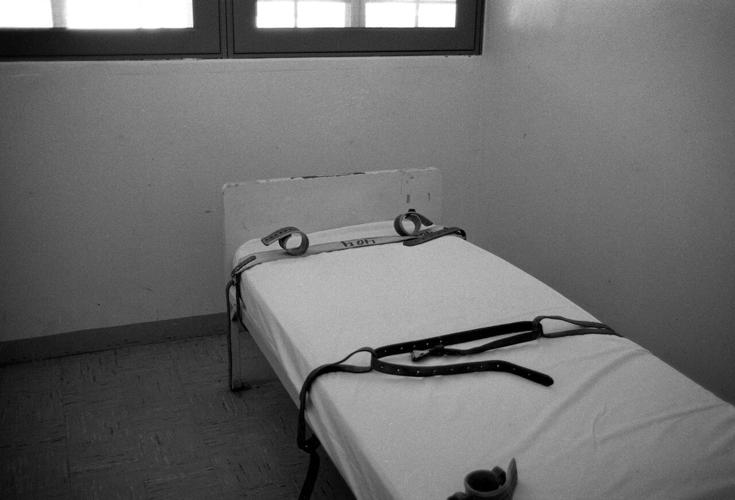

”The Room” Metro State Hospital, Norwalk, 1979. Photo by Merrick Morton

What was your first paid job?

My first professional job was in 1979. I got a California State grant to shoot at the Metropolitan State Hospital in Norwalk, a psychiatric hospital and this was to recruit volunteers to come in and spend time with the patients at the hospital. I got that through someone who my cousin was friends with. I approached them and I was able to get a grant to do an audio visual slideshow. It was supposed to be maybe three or four weeks shooting.

I told the front office that I would be coming in at different times of the day and on weekends, so they issued me a pass key so I could go in and out anytime. I ended up getting lost in the system and was there for about a year and a half, just shooting. But one day, on a Sunday, someone got stabbed and was being carried down the hallway and put in restraints. Someone on the staff was not comfortable with me photographing that, so they wanted my film. I handed them a roll of film, but not the one I was shooting. I had switched them. The next day I got a call from the hospital, saying that I wasn’t supposed to be there anymore, the job ended a long time ago and I couldn’t come back.

I think I've always gravitated to subjects I'm not supposed to do.

”Dancing on the Malecón” Havana, Cuba, 1998. Photo by Merrick Morton

How and when did you get interested in cholo culture?

In 1980, I became aware of the cholo culture and that was through an artist I met, John Valadez. I'm not sure how I got his contact, but I made it to his studio, which at the time was on 3rd Street and Broadway in downtown LA. I saw some of his artwork and I said, my God, I would love to try to photograph the people he shows in his work.

That was the catalyst for me to really [try] to learn about the culture, trying to find out where I could go to shoot. I would drive around, and I'd see graffiti, but I didn't know more than that.

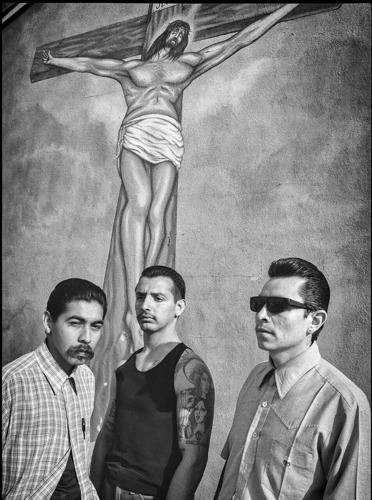

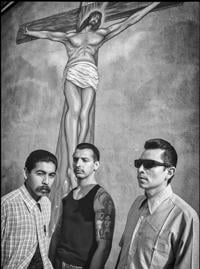

”White Fence” East Los Angeles, 1986" Photo by Merrick Morton

I started to research on how to find this culture I didn't know anything about. I made calls to everybody I could think of. I ended up calling L.A. County Probation to see if there was some way to go out on a ride-along. They hooked me up with someone and his caseload was in East L.A. That was in 1980, the first time that I was really out in the barrio to really explore. It started at the handball courts at Obregón Park. I set up a little studio with a drop cloth in their rec center. From there I was able to hit the streets. I'd hand out photography, [using it] like business cards. Later, I’d go back into the neighborhood, and I bring them the prints. I would see people on the street sometimes and stop and say this is some of the work I do. I did some ride-alongs with LAPD gang detail and youth gang services, a gang diversion program where ex-gang members would work with gangs, trying to stop problems.

What was your approach in taking photos in the streets?

It was really showing my photography first: “This is what I do” and them figuring out what they would get out of it. But basically, I guess they saw me as someone really trying to document their culture. I think they also enjoyed receiving photographs that they could keep for themselves and their families. So probably, I was an oddity, too, because, you know, it's just white guy going out to the barrio in the inner city. I think they maybe found that strange, too. Why is he out here? But there was very little pushback. Sometimes they’d ask to get paid, but I just told them that I can’t pay. That would shut that down.

Certain times, I just went out there. I shot some stuff on a street corner and then I’d go [back to the same corner]. I would make friends with certain people, and they would have me over their house and I’d get to see family situations. When I first started shooting street gangs, I had the perception that I'm going to be shooting this violent world. I quickly learned that the violent aspect of it is a very small part of what goes on every day. I mean, things happen. People get killed. But again, that's a very small part of the day-to-day lifestyle. The family being so close, seeing the family unit was enjoyable for me and I think an inspiration to try to capture more of that.

”A Mother Embraces Her Son” Venice 13, 1988. Photo by Merrick Morton

I like my work to be one-on-one. Although I do some candid [unposed] photography, in almost all my work I’m shooting someone who’s very aware and in front of me. I want them to be aware of me and I want them to be aware of the camera. I consider my work more street portraiture as opposed to just street photography. I do have some candid work but generally I’m trying to capture some sort of relationship. It's almost always momentary but it's still a relationship. I also like to think that they’d take some sense of pride that someone is capturing their cultural heritage.

When and how did you get started in the movie industry?

During the 80s, I began to shoot Black culture, too, and took photographs in Mexico. I was able to show some of my gang work and Mexico photos to the producer of the “La Bamba,” Taylor Hackford. They already had a still photographer working for them, so they hired me as a second photographer. It was interesting that Luis Valdez was the director of “La Bamba,” he was the creator of “Zoot Suit,” which was an early inspiration for my work. It was like a full circle. By working on the film, I was also fortunate to get into the union, which is very hard. A memory of shooting “La Bamba” is how deeply [Richie Valens’] family was involved. They were always there. I really found that interesting because the film itself had this very family feeling to it. The real Bob was there, the sisters were there, even the mother was there. It was interesting to see the dynamics.

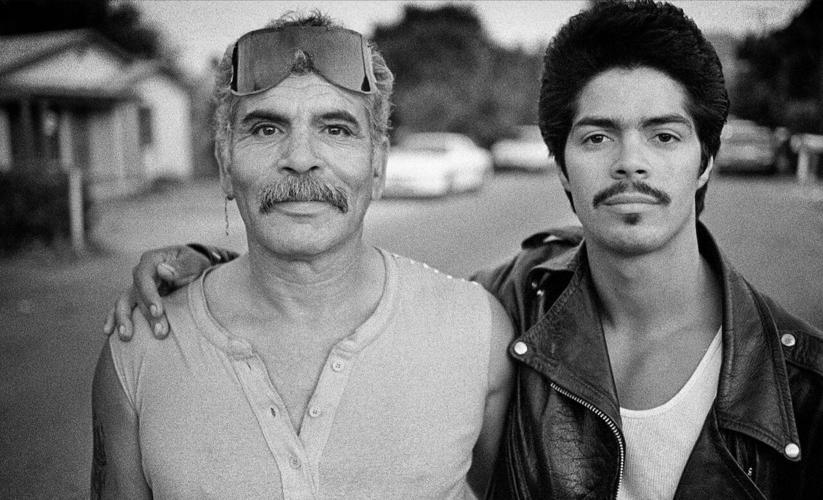

"La Bamba: The Two Bobs” Bob Morales & Esai Morales, 1986

Shooting in San Quentin for “Blood In, Blood Out” was really interesting to me, too. We were there for six weeks. Being on the main line, meeting all these people and seeing the interaction between actors and extras and the inmates at the time, that was interesting.

I'm still shooting for feature films, shooting some series for HBO. COVID hit and that slowed things down and then the strike. Now things are starting to pick up more so again I'm sort of making the rounds, showing my work again.

Do you miss shooting in the streets?

Yeah, but through Instagram, people have contacted me, saying “Oh, that's my cousin or uncle … that's my father.” I've been able to reconnect and really take to the streets again. I took about a probably 25-year break, but through Instagram, it gives me the desire to go out and photograph friends again and go to neighborhoods again.

"Valentina" Los Angeles, 2022. Photo by Merrick Morton

Also, I was fortunate to be invited by photographer Frankie Orozco who has this event once a year called “2 Live and Die in LA.” He saw some of my work two years ago and invited me to participate. That really helped me meet other people. I’m thankful to him for helping my career outside of the film world. Through him and with other people, we started this group of street photographers called The L.A. Six. Some would consider it maybe the fringe of LA, but it seems to work well.

I like the idea of going out and shooting again, yeah, because for me I like the idea of not knowing what I'm going to create. I'm always wondering what I’m going to come up with next.

“Merrick Morton: Un-Rehearsed” is at Eastern Projects, 900 N. Broadway, #1090, Los Angeles, CA 90012. Open Tuesday through Saturday, 10am to 6pm. On view through May 18, 2024. EasternProjectsGallery.com

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.